As inquisitive children at Killowen School in the late 1950s, we discovered at a distance handloom weaving. The new building behind the school, known as Hay-Edie’s factory was high above with a window facing down. A girl was working on a handloom. We could hear rhythmical repetitive sounds. Sometimes the girls would spot us and wave down at us before our teacher called us back to class. In school, we did know something about tweed as we made pictures from bits of fabric in craft class. Everybody seemed to have thatched cottages in their pictures, set in different colourful fields with oversized, fluffy sheep and mountains that looked more like the Alps than the Mournes.

Some years later, at the age of seventeen, in the late 1960s, I became one of the workers at Hay-Edies factory or Mourne Textiles, to use its proper name. My first impression on entry was the smell of oily yarn. It reminded me of newly-shorn sheep that we had on the farm at home.

Mrs Hay-Edie, the owner of the establishment gave all new recruits an induction, and almost immediately I was shown how to make bobbins for weavers upstairs. I was also taught how to make all the important knots: weavers knots for finer yarns like 8 cut and the reef knot for thicker yarns such as carpet yarn or 4 ½ cut.

The next job was to learn how to make cheeses (spools of yarn). The yarn sometimes came on hanks, which were stretched over the wooden wheel-like thing and the machine winded the yarn onto cheeses. Three were made at the same time, like the bobbin machine. Cheeses had to be a certain weight and were used in the warp making process. Weighing was constant and important before and after warp making to establish the amount used. Mrs Hay-Edie made the warps herself and would have spotted badly made knots or a cheese running out when it wasn’t the correct weight.

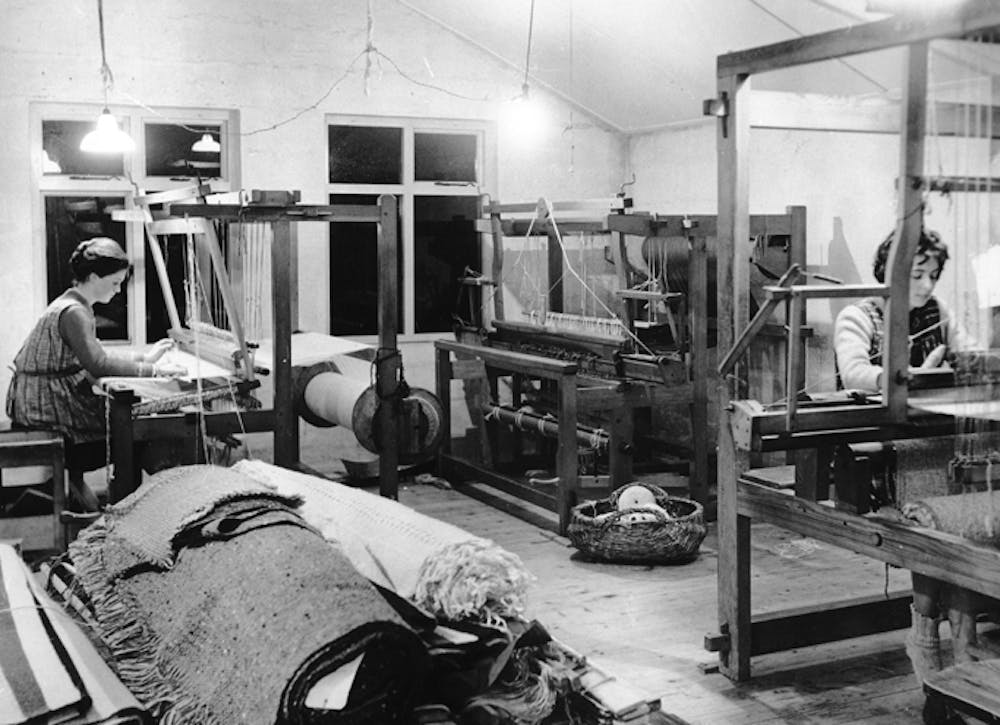

There were three girls working in the workshop: Mary, Rose and Breda. Later on, a man came to weave who had been there before. His name was Oliver. He was regarded as a very good weaver.

As I was the last worker in, I had other tasks as well. At 8:30am, I would collect the key of the workshop from the Hay Edie’s private residence and have it opened for the other workers when work started at 8:45am. In cold weather, I had to fill oil stoves with paraffin oil outside and then have them placed and lit in various points in the workshop to provide heat.

Making tea at 10:30am and 3:30pm was another duty; the tea, milk and sugar were supplied. Lunch break was from 1pm to 1:45pm. I lived down the road and was able to have my lunch there. Brushing up was also my job and this started at 5:30pm. Work finished at 5:45pm, Monday to Friday. A lot of yarn ends had gathered along with dust and fluff from the day’s work and on a Friday morning, this was burned outside.

Almost every week, Mrs Hay-Edie took the rolls of oily woven tweed in her little Morris traveller car (one with the wood in the bodywork) to be washed in Belfast. When on her journey there, she collected stocks of yarn from Newtownards. It was my job to unload the car the next morning, weighing all the new yarn, labelling it and entering the descriptions etc. into the yarn stock book.

When the newly washed tweed returned, great care had to be taken when unloading and weighing again before the fabric was mended, that is opening all the knots and snipping off the ends. The fabric was now finished and placed in the showroom upstairs. The showroom displayed all the finished products of dress material and furnishing fabrics as well as rugs. At the end of all rolls, the distinctive white label with the sketch of the goat was places. Many people visited the showroom and purchased there. Among those who called in were acclaimed fashion designers, Sheila Mullaley and Sybil Connolly from Dublin. They both used Mrs Hay-Edie’s unique fabric in their collections.

Eventually, I was entrusted to learn how to weave. There were many parts of the loom to learn: the reed and the heedles, to the beam and the peddles. From memory, I think I wove furnishing fabric on the wide loom and dress fabric on the Norwegian loom. Although my time at the workshop was only a few years, it was my first paid job and I will always remember it fondly. Nearly everything Mrs Hay-Edie taught me of her craft remained with me.

Over forty years later, I still call into the workshop that has changed in layout and is much bigger. The weaving continues under the expertise of Mrs Hay-Edie’s daughter Karen and grandson Mario and their weavers. Mario has introduced the internet and digital age for communication and marketing purposes, alongside the original looms and various pieces of equipment that never change. And the children are still playing behind the school below, just as inquisitive as ever.